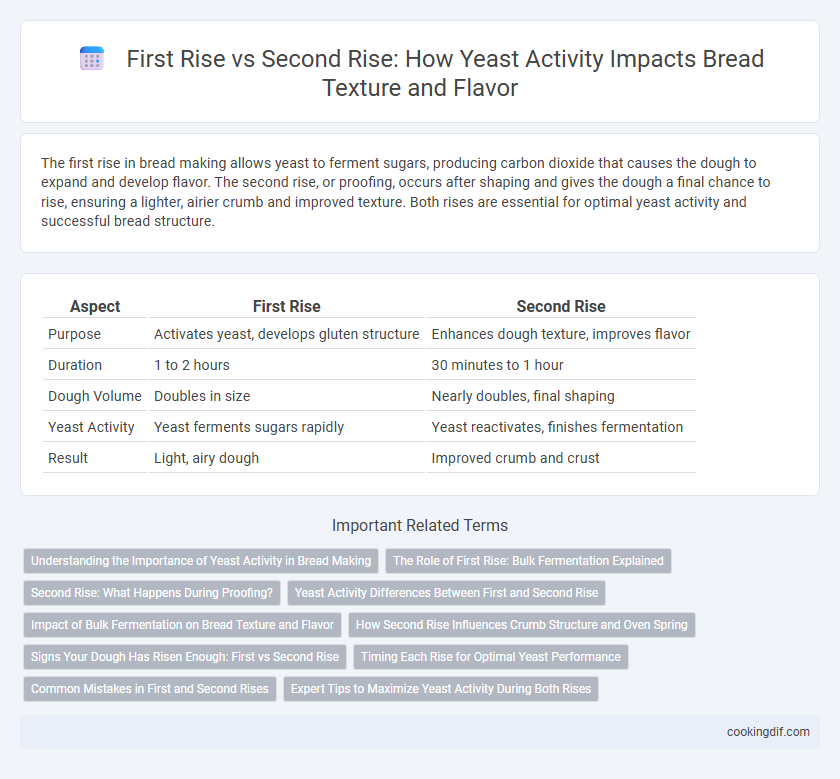

The first rise in bread making allows yeast to ferment sugars, producing carbon dioxide that causes the dough to expand and develop flavor. The second rise, or proofing, occurs after shaping and gives the dough a final chance to rise, ensuring a lighter, airier crumb and improved texture. Both rises are essential for optimal yeast activity and successful bread structure.

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | First Rise | Second Rise |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Activates yeast, develops gluten structure | Enhances dough texture, improves flavor |

| Duration | 1 to 2 hours | 30 minutes to 1 hour |

| Dough Volume | Doubles in size | Nearly doubles, final shaping |

| Yeast Activity | Yeast ferments sugars rapidly | Yeast reactivates, finishes fermentation |

| Result | Light, airy dough | Improved crumb and crust |

Understanding the Importance of Yeast Activity in Bread Making

Yeast activity during the first rise, or fermentation, develops flavor and texture by producing carbon dioxide and alcohol, which create air pockets essential for bread structure. The second rise, or proofing, allows the dough to expand further, enhancing volume and softness before baking. Proper control of both rises optimizes gluten development, yeast metabolism, and dough elasticity, resulting in superior crumb and crust quality.

The Role of First Rise: Bulk Fermentation Explained

The first rise, known as bulk fermentation, is crucial in bread-making as it allows yeast to metabolize sugars and produce carbon dioxide, which creates the dough's initial volume and gluten structure. During bulk fermentation, enzyme activity breaks down starches and proteins, enhancing flavor development and dough extensibility. This stage sets the foundation for the second rise by strengthening gluten networks and increasing yeast activity, ensuring optimal gas retention in the final proofing phase.

Second Rise: What Happens During Proofing?

During the second rise, or proofing, yeast activity resumes as the dough rests after shaping, allowing the yeast to ferment sugars and produce carbon dioxide gas. This gas expands the gluten network, resulting in a lighter, more aerated crumb structure and enhanced dough elasticity. Proofing also intensifies flavor development by prolonging fermentation and increasing organic acid production.

Yeast Activity Differences Between First and Second Rise

During the first rise, yeast activity is vigorous as the yeast ferments sugars, producing carbon dioxide that causes the dough to expand and develop gluten structure. The second rise, or proofing, involves slower yeast activity, allowing the dough to mature, flavors to deepen, and texture to improve before baking. Differences in yeast activity between these stages impact bread's volume, crumb consistency, and overall quality.

Impact of Bulk Fermentation on Bread Texture and Flavor

Bulk fermentation, or the first rise, allows yeast to produce carbon dioxide and organic acids that develop complex flavors and improve crumb structure in bread. During this phase, gluten networks strengthen, resulting in better dough elasticity and a more open, airy texture. The second rise, or proofing, mainly fine-tunes volume and surface tension, but the bulk fermentation period has the most significant impact on overall bread texture and flavor depth.

How Second Rise Influences Crumb Structure and Oven Spring

The second rise, also known as the proofing stage, allows yeast activity to produce more carbon dioxide, which significantly enhances oven spring by creating a lighter, airier loaf. This additional fermentation strengthens the gluten network, resulting in a more open crumb structure with improved texture and chewiness. Properly timed second rise maximizes volume and prevents dense, under-risen bread commonly seen after only a single rise.

Signs Your Dough Has Risen Enough: First vs Second Rise

During the first rise, dough typically doubles in size and shows visible air bubbles on the surface, signaling active yeast fermentation and sufficient gluten development. The second rise, or proofing, often appears less dramatic but dough should puff up noticeably and retain a slight indentation when gently pressed, indicating optimal yeast activity for baking. Monitoring these signs ensures a well-risen dough with improved texture and flavor in the final bread.

Timing Each Rise for Optimal Yeast Performance

Timing the first rise between 1 to 2 hours allows yeast to ferment sugars effectively, producing carbon dioxide that helps dough expand. The second rise, typically 30 to 60 minutes, enables the dough to develop finer texture and improved crumb structure before baking. Monitoring temperature between 75degF to 80degF during both rises ensures optimal yeast activity and dough consistency.

Common Mistakes in First and Second Rises

Overproofing during the first rise can exhaust yeast activity, resulting in dense bread with poor oven spring. Neglecting to punch down the dough after the first rise often causes uneven gas distribution, leading to irregular crumb texture. Allowing the second rise to extend too long can cause the dough to collapse, while insufficient second rising time prevents proper dough expansion and flavor development.

Expert Tips to Maximize Yeast Activity During Both Rises

Maximizing yeast activity during the first rise involves maintaining a warm environment between 75-85degF (24-29degC) and ensuring dough hydration at around 65-70%, which promotes optimal yeast fermentation and gas production. For the second rise, gently degassing the dough and proofing at slightly cooler temperatures (70-75degF or 21-24degC) helps strengthen gluten structure and enhances dough flavor development. Expert bakers recommend using a proofing box or covering dough with a damp cloth to maintain consistent humidity, crucial for preventing crust formation and supporting expansive yeast activity throughout both fermentation stages.

First Rise vs Second Rise for yeast activity Infographic

cookingdif.com

cookingdif.com