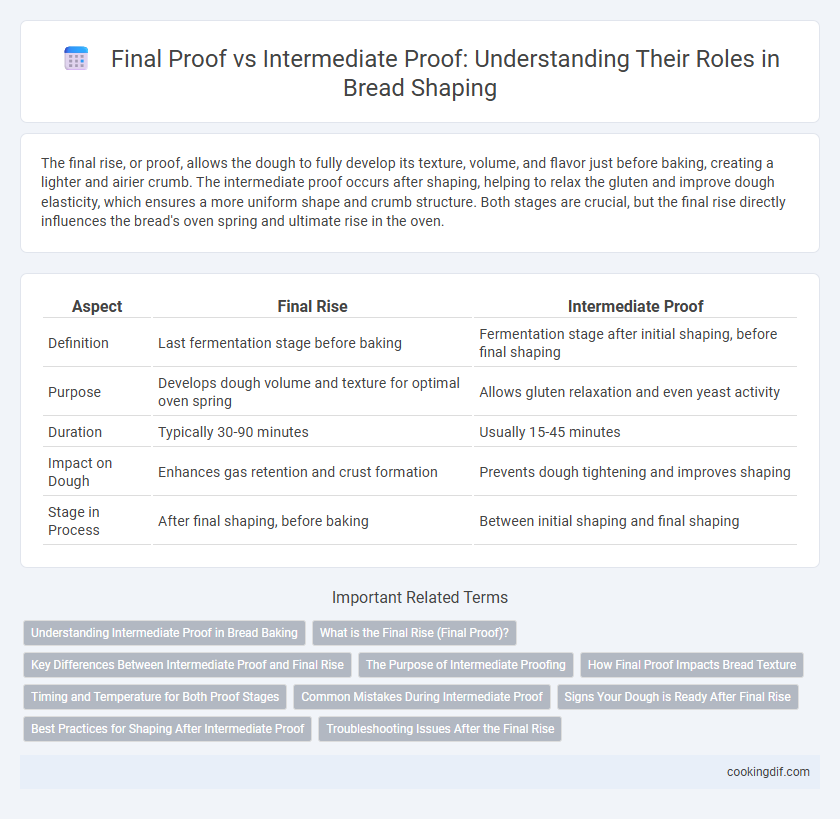

The final rise, or proof, allows the dough to fully develop its texture, volume, and flavor just before baking, creating a lighter and airier crumb. The intermediate proof occurs after shaping, helping to relax the gluten and improve dough elasticity, which ensures a more uniform shape and crumb structure. Both stages are crucial, but the final rise directly influences the bread's oven spring and ultimate rise in the oven.

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Final Rise | Intermediate Proof |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Last fermentation stage before baking | Fermentation stage after initial shaping, before final shaping |

| Purpose | Develops dough volume and texture for optimal oven spring | Allows gluten relaxation and even yeast activity |

| Duration | Typically 30-90 minutes | Usually 15-45 minutes |

| Impact on Dough | Enhances gas retention and crust formation | Prevents dough tightening and improves shaping |

| Stage in Process | After final shaping, before baking | Between initial shaping and final shaping |

Understanding Intermediate Proof in Bread Baking

Intermediate proof is a crucial step in bread baking that allows dough to develop optimal gluten structure and flavor before shaping. This phase typically occurs after the initial bulk fermentation, where the dough is gently folded or rested to redistribute yeast activity and gases. Understanding the role of intermediate proof helps prevent over-proofing, ensuring a stronger final rise and improved crumb texture in the finished bread.

What is the Final Rise (Final Proof)?

The final rise, or final proof, is the last stage of fermentation where shaped dough undergoes its final expansion before baking, allowing yeast to produce carbon dioxide and create an airy crumb structure. This stage significantly influences the bread's volume, texture, and flavor development. Unlike the intermediate proof, which occurs before shaping and helps strengthen gluten, the final proof ensures the dough has reached optimal gas retention for a light and well-risen loaf.

Key Differences Between Intermediate Proof and Final Rise

Intermediate proof occurs before shaping and allows the dough to develop gluten structure and gas retention, while the final rise happens after shaping to achieve optimal volume and surface tension. Intermediate proof typically lasts longer to strengthen the dough, whereas the final rise is shorter and focuses on controlled expansion. The key differences lie in the timing, duration, and purpose within the bread-making process, impacting texture and crumb development.

The Purpose of Intermediate Proofing

Intermediate proofing allows dough to develop essential gluten structure and improve gas retention before shaping, ensuring a more uniform grain and better oven spring during the final rise. This stage controls fermentation activity, preventing over-proofing and enabling easier handling and shaping of the dough. Proper intermediate proofing ultimately enhances the texture and volume of the finished bread.

How Final Proof Impacts Bread Texture

Final proof significantly influences bread texture by allowing yeast activity to create gas bubbles that expand the dough, resulting in a lighter, airier crumb. During the final rise, gluten strands relax and stretch, improving dough elasticity and crumb structure. In contrast, the intermediate proof mainly develops flavor and fermentation but has less impact on the dough's ultimate volume and texture.

Timing and Temperature for Both Proof Stages

During the final rise, bread dough is typically proofed at a slightly warmer temperature around 75-80degF (24-27degC) for 45-60 minutes to achieve optimal volume and gluten relaxation. The intermediate proof, occurring after the initial fermentation and before shaping, is usually done at cooler temperatures near 68-72degF (20-22degC) for 30-45 minutes to develop flavor and dough strength without over-expansion. Precise timing and temperature control during both proof stages ensure balanced fermentation, improved crumb structure, and enhanced aroma in the finished loaf.

Common Mistakes During Intermediate Proof

During the intermediate proof, common mistakes include overproofing or underproofing, which can lead to poor dough structure and uneven crumb texture. Failing to deflate the dough properly after the intermediate proof can cause irregular shaping and dense bread during the final rise. Precise control of temperature and humidity is crucial to avoid these issues and ensure an optimal final rise for perfect bread quality.

Signs Your Dough is Ready After Final Rise

The final rise, or proof, is crucial for achieving optimal bread texture, indicated by dough that springs back slowly when gently pressed and retains a slight indentation. This stage differs from the intermediate proof, where the dough is bulk fermented and less airy, primarily for gluten development and flavor enhancement. Recognizing these signs after the final rise ensures proper shaping and baking for a well-risen loaf with a light crumb and crisp crust.

Best Practices for Shaping After Intermediate Proof

For optimal shaping after the intermediate proof, handle the dough gently to preserve gas bubbles formed during fermentation, which enhances crumb structure and oven spring. Use minimal flour on the work surface and avoid degassing too aggressively to maintain dough elasticity and improve final volume. Shaping techniques such as folding or rounding should create surface tension without tearing the dough, preparing it for the final rise that maximizes loaf height and texture.

Troubleshooting Issues After the Final Rise

Issues after the final rise in bread baking often stem from overproofing or underproofing, causing collapsed loaves or dense crumb structure. Proper timing and temperature control during the intermediate proof help develop gluten strength, preventing dough from losing gas retention during the final rise. Adjusting proofing times based on dough behavior ensures optimal oven spring and loaf volume after shaping.

Final rise vs intermediate proof for shaping Infographic

cookingdif.com

cookingdif.com