A roux and a slurry are both effective thickening agents for casseroles but differ in preparation and texture outcome. A roux is made by cooking equal parts flour and fat, which adds a rich, nutty flavor and smooth consistency, ideal for creamy casseroles. A slurry combines cold water with cornstarch or flour, creating a quick, clear thickener that is perfect for dishes requiring a glossy finish without altering the base flavor.

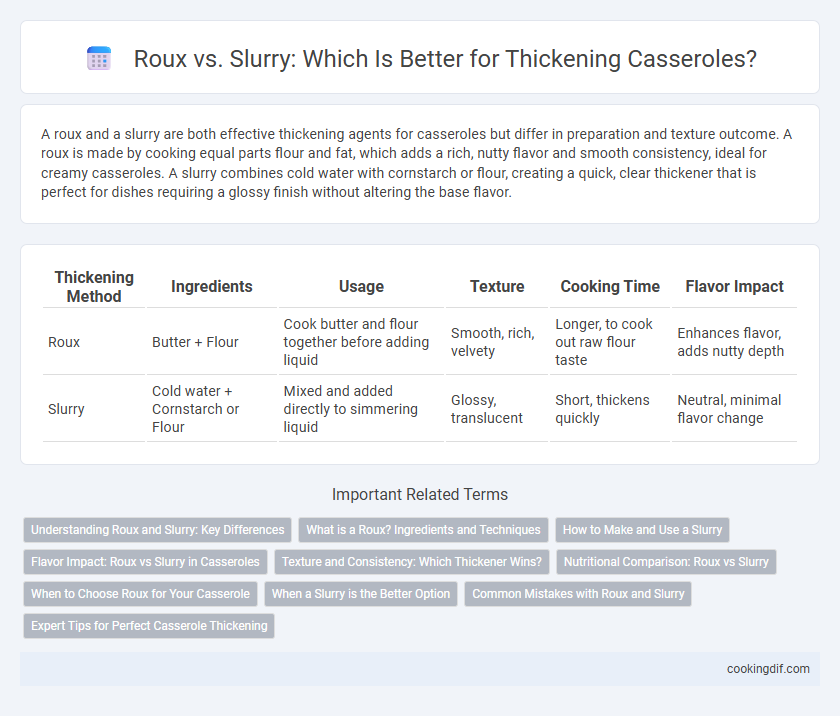

Table of Comparison

| Thickening Method | Ingredients | Usage | Texture | Cooking Time | Flavor Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roux | Butter + Flour | Cook butter and flour together before adding liquid | Smooth, rich, velvety | Longer, to cook out raw flour taste | Enhances flavor, adds nutty depth |

| Slurry | Cold water + Cornstarch or Flour | Mixed and added directly to simmering liquid | Glossy, translucent | Short, thickens quickly | Neutral, minimal flavor change |

Understanding Roux and Slurry: Key Differences

Roux and slurry are two primary methods for thickening casseroles, each with distinct characteristics and applications. Roux, a mixture of fat and flour cooked together, develops a rich, nutty flavor and provides a smooth, velvety texture, making it ideal for dishes requiring deeper flavor profiles. Slurry, composed of cornstarch or flour combined with cold water, offers a quicker, more neutral thickening option that yields a glossy, translucent finish without altering the dish's flavor significantly.

What is a Roux? Ingredients and Techniques

A roux is a classic thickening agent made from equal parts fat, typically butter, and flour cooked together to form a smooth paste used in casseroles to create rich, velvety sauces. The process involves gently cooking the fat and flour over medium heat to eliminate the raw flour taste, with cooking time affecting the roux's color and flavor intensity--from pale blonde for mild thickening to deep brown for robust flavor. Mastery of roux technique ensures proper thickening and consistency in casserole dishes, differentiating it from a slurry, which is a simple uncooked mixture of flour or cornstarch and liquid.

How to Make and Use a Slurry

A slurry is made by mixing equal parts cold water and a starch, such as cornstarch or flour, until smooth, then slowly incorporated into a simmering casserole to thicken the sauce without lumps. It is essential to add the slurry gradually while stirring continuously to achieve the desired consistency and prevent clumping. This method allows for precise control over thickness and creates a glossy, smooth texture ideal for casseroles.

Flavor Impact: Roux vs Slurry in Casseroles

Roux enhances casserole flavor by cooking flour in fat, developing a rich, nutty taste that deepens the dish's overall profile. Slurry, a mixture of starch and cold liquid, thickens casseroles quickly without altering the base flavor, maintaining a cleaner, more neutral taste. Choosing roux contributes to complex layers of flavor, while slurry preserves the casserole's original ingredients' true essence.

Texture and Consistency: Which Thickener Wins?

Roux and slurry both serve as popular thickeners in casseroles, but roux offers a richer, silkier texture with a more uniform consistency due to its blend of flour cooked in fat. Slurry, made from cornstarch or flour mixed with water, provides a clearer, glossy finish and thickens more quickly but can result in a slightly gelatinous texture. For casseroles requiring a creamy, smooth mouthfeel, roux generally wins, while slurry is preferred for lighter, more translucent sauces.

Nutritional Comparison: Roux vs Slurry

A roux, made from equal parts flour and fat, typically adds more calories and fat content compared to a slurry, which is a mixture of starch and cold water with minimal calories and fat. Slurries, often using cornstarch or arrowroot, provide a gluten-free alternative with fewer carbohydrates and less fat, making them suitable for lighter casserole preparations. Nutritionally, choosing a slurry over a roux can reduce saturated fat intake and overall caloric density while still achieving effective thickening.

When to Choose Roux for Your Casserole

Roux is ideal for casseroles requiring a rich, creamy texture and a deep, complex flavor, as it involves cooking equal parts flour and fat to develop a nutty taste. Use roux when you want a smooth, velvety sauce that won't break down during long baking times or high heat. It provides better stability and thickness compared to a slurry, making it perfect for classic dishes like chicken pot pie or creamy vegetable casseroles.

When a Slurry is the Better Option

Slurry is the better option for thickening casseroles when a clear, glossy finish is desired and the mixture is already hot. It dissolves quickly without creating lumps, making it ideal for delicate sauces or when last-minute thickening is needed. Unlike roux, slurry does not add fat, preserving the casserole's original flavor profile and texture.

Common Mistakes with Roux and Slurry

Common mistakes with roux include overheating, which causes a burnt taste and darkens the color, and incorrect flour-to-fat ratio resulting in a lumpy or greasy texture. Slurry errors often involve adding it too quickly or to boiling liquids, causing clumping or loss of thickening power. Proper temperature control and gradual incorporation of both roux and slurry ensure smooth, consistent casserole sauces.

Expert Tips for Perfect Casserole Thickening

Roux, a cooked mixture of flour and fat, provides a rich, velvety thickness and depth of flavor ideal for casseroles, while slurry, a combination of cornstarch and cold water, offers a quicker thickening method with a glossy finish. Expert tips recommend cooking the roux thoroughly to eliminate raw flour taste and gradually adding liquid to avoid lumps, whereas slurry should be added slowly to simmering liquids to activate thickening without clumping. For consistent casserole thickening, roux is preferred for creamy, complex sauces, while slurry suits lighter, clearer textures.

Roux vs slurry for thickening Infographic

cookingdif.com

cookingdif.com